How Wiredcraft Helped Register 35M Voters Across Myanmar

Connecting the Disconnected

Wiredcraft has been working with IFES (International Foundation for Election Systems) and the Myanmar UEC (Union Election Commission) to build the software supporting the November 8th Myanmar elections - the first democratic elections in Myanmar in over 20 years. Wiredcraft won the contract competitively to design VL software; the database and software is owned and maintained by the UEC.

I recently presented a talk at the Shanghai Barcamp that shared the technology behind the work that Wiredcraft did registering 35 million voters in Myanmar. I’ve provided a behind-the-scenes look into the voter registration, including challenges we had to overcome.

The UEC is required by law to create the voter registration lists by inputting GAD (General Administration Department) and immigration logbooks. We then created both the system that would consolidate all the voter list data into one central database, together with the software that enables the UEC teams to correct and edit the voter database at the local level, TVR (Township Voter Registration System).

We built the “Check My Name” app and the TVR, so that citizens would have access to verify, edit, or add data to the official voter database. We accomplished this through the following.

How Did Voters Check Their Information?

- Online access: We built the “Check My Name” website for the UEC to maintain as a public platform for voters to access their registration information. Through the software, citizens had access to their registered information and could submit changes to the UEC members at their local Township office. We provided on-the-ground training to help the UEC staff members use the Township Voter Registration (TVR) Software.

- Offline access: Each township had a local UEC office which posted printed lists of people’s registration information.

How Did UEC Staff Help Voters Edits their Information?

- Initially the data was edited at a local level through the TVR app. Citizens would submit the legal forms (outlined in the “Building the Voter Registration for the Myanmar Elections” blog post) with the help of UEC Staff members. The UEC staff would then input the forms and verify the information.

- The gathered information was then sent to the central voter registration system to make sure their was no conflicting or duplicate information and then was sent to the ACL, the permission layer, that granted access and control of the lists so that only limited administrators had access to features for profiles and limited clerical permissions.

Technical Obstacles to overcome in Myanmar

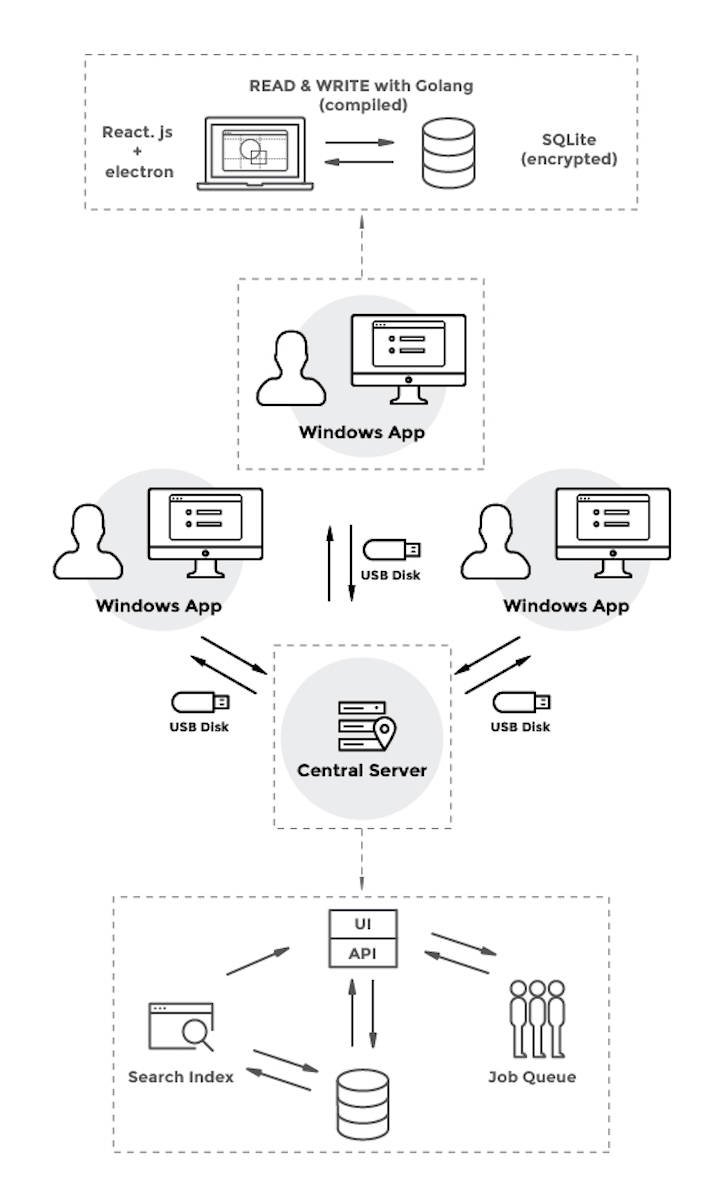

- The voter registration data collection that happened at the local township level needed to be transferred securely to a central location and input into the central voter registration database to ensure no duplicate entries, incorrect formatting or overwrites.

- No network connection. Myanmar’s physical infrastructure limits the transfer of data online (no 3G coverage); meaning that the data for voter registration needed to be transferred offline through USB drives. Offline data transfer involved using data packaging, data encryption, etc

- Since the data collection happened over a few weeks time nationwide the data had to be transferred a few times a month. This meant large amounts of data was traveling back and forth to ensure the sanity of the data.

- 100% accuracy and security.

- Limited hardware power due to limitations on hardware importation to Myanmar.

- Heavy aggregation needs for the reports.

The Stack

Key Points for Technical Support

The following are the key concepts that provided the technical support to keep the software running securely and reliably. “Distributed” between central system (1 database) and township level system (many databases).

Global Uniqueness

- UID for the data that never or barely change, for example, the Townships.

- UUID for the data that always changes like the individual registrant’s data.

We didn’t push this concept to everything initially, which became a problem later on. For example, we didn’t have UUIDs for the polling stations, but this became an issue when we needed to have a complete database of the polling stations. It was possible to obtain this information by aggregating from registrant’s information or creating a database on the central server, but there would be a high possibility of errors or duplicates with these methods. So we fixed this issue by applying UUIDs to each polling station, and pushing the concept to the rest of the project.

Race Conditions - Why UUID and why UID is not enough?

Difference is UID is assigned in the central voter registration system while UUID is assigned at the township level (with the Windows app). The distributed system caused an issue with the IDs since the data was collected at the township level and then transferred to the central system. We couldn’t rely on the central system to assign IDs for the incoming data because multiple data packages could be imported at the same time from the township levels.

Security

Encryption is important for all elections and personal data.

- Encrypted SQLite + compiled with Golang. This makes it very difficult to hack either the database or the process that grants access to the database.

- GunPG. Each township received their own encryption keys so that the voter registration information could be only opened by the local window apps or the central system. Also staff members from different places can’t exchange data, this was implemented to avoid cross pollination of data and to ensure we could establish the source of the data.

Celery

- HTTP request can timeout due to a lack of power (server side). We solved this by putting the operation in a task and then saved the task ID, returned the task reference. If necessary, we let the UI check the result once a few seconds until it finished the task, to help the server.

- Terminal server-side was out-of-memory because there was too much data so we avoided commands and instead used HTTP request + tasks.

- Concurrency was both an optimization and a limitation. Some of the heavy jobs like finding duplicate registration information like the NRC (National ID Number) Number) could be done more quickly. But was limited because a lot of the data was being pushed at the same time, there was a possibility that the operations could be overloaded.

We found it important to utilize caution with aggregations.

- ElasticSearch is powerful and convenient, but it eats too much memory, (which we didn’t have to spare).

- Celery, sometimes we had to use something simpler and much slower, and we need to rely on the job queue. For example, we wanted to find out which people registered twice with some certain info (for example NRC number). It’d be quicker to have ElasticSearch to do an aggregation but it costs too much power and kills the server, so we had to loop through the entire database to find out, which then can cost time, up to days or weeks. Our solution was to split the task and put them in the task queue and which limited the cost of time to a day. Which wasn’t the most optimal solution but was able to solve the problem at hand with limited wasted resources.

A lot of technology went into making the Myanmar elections possible. Technology can be a vital tool for newly forming democracies to take advantage of transparency and accountability in the election and registration processes. More on information about our work on the Myanmar elections see “Building the Voter Registration for the Myanmar Elections”.