Improving your communication by following the Pyramid Principle

Logic in writing, thinking and problem solving.

Communication is more than just talking with each other. It is a two-way process for the purpose of reaching mutual understanding between one and the other. Marshall Rosenberg encourages us to communicate with compassion in her book Nonviolent Communication. When it comes to communication in the workplace, communicating effectively with our colleagues plays a critical role in delivering good work. Miscommunication leads to misunderstanding, which frustrates everyone.

But how can we ensure that we are good communicators in the workplace? The Pyramid Principle® by ex-McKinsey consultant Barbara Minto, offers an insightful answer to this question. I read this book last year, and it influenced my opinion remarkably upon communication. I’m still trying to put theories and frameworks mentioned in the book into practice. Thus, I’m writing this blog post, which introduces you to three key elements in the Pyramid Principle, to help organize your thinking so that the ideas you present can be easily absorbed by the audience:

- Ordering from the Top Down

- Thinking from the Bottom Up

- How to write an Introduction

Ordering from the Top Down

The Pyramid Principle® advocates that “ideas in writing should always form a pyramid under a single thought”. Underneath the single thought, group and summarize the next level of supporting ideas and arguments. This not only applies to writing, but also works for verbal communication. Controlling the sequence of how you present your ideas is very important. In most cases, we are used to listing a series of points and ending with the conclusion. However, presenting ideas like this is not straightforward. Executives can only get your point after listening to your full presentation, which is not efficient.

Here’s an example: it is very common to be asked, ‘How is your progress on X?’ Compare the two answers below:

- Example 1: “umm, we’re checking the summer campaign data in Google Analytics. However we’re not sure about the date range, need to check with the marketing team. I have already sent an email, and am now waiting for their reply.”

- Example 2: “It’s almost done. Just need to check the campaign date with the marketing team. I’m waiting for their reply. ”

How do you feel about these two answers? We tend to answer like the first example, focusing on what we’re doing now. However, the person who raises the question wants to know about the overall progress - the big picture. In example 2, the first sentence ‘it’s almost done’ is a straightforward answer, and it gives the conversation partner an instant impression. Then it naturally leads to the next level - the reason behind why ‘it is almost done’. And then you offer the necessary details. Presenting ideas like this makes communication more efficient because people don’t struggle to figure out what you’re trying to tell them.

As the Pyramid Principle advocates, the ideal sequence is to give the summarizing idea first and then group and summarize the supporting arguments afterwards. This applies everywhere - from when you are answering a question from an executive, to addressing an issue in an email - pretty much almost everywhere in workplace communication.

To summarize, ordering from the top down is to:

- Pay attention to the sequence when you present your ideas

- Give the summarized idea at the beginning

- Group and summarize the supporting arguments afterwards

Thinking from the Bottom Up

For more complicated work like preparing a proposal, if you are not able to come up with a single thought immediately, write down all your ideas and try to sort out the relationships between them. Then, you can draw conclusions. Here we are going to talk about two types of logical relationships in a grouping - deduction and induction.

Deductive reasoning works from the general to the specific, presenting an argument in successive steps. See the example below:

- Men are mortal.

- Socrates is a man.

- Therefore Socrates is mortal.

Inductive reasoning, by contrast, works from specific instances to a generalized conclusion. Thus, the form of this argument would be:

- French tanks are at the Polish border.

- German tanks are at the Polish border.

- Russian tanks are at the Polish border.

Then, based on these statements, we draw an inference - “Poland is about to be invaded by tanks”.

Whether you are doing either deductive or inductive reasoning, make sure your ideas are in a logical order. The validity of a premise also affects the conclusion. If you want to learn more logic principles, the book Logic: A Very Short Introduction from Oxford University Press is highly recommended.

How to write an introduction

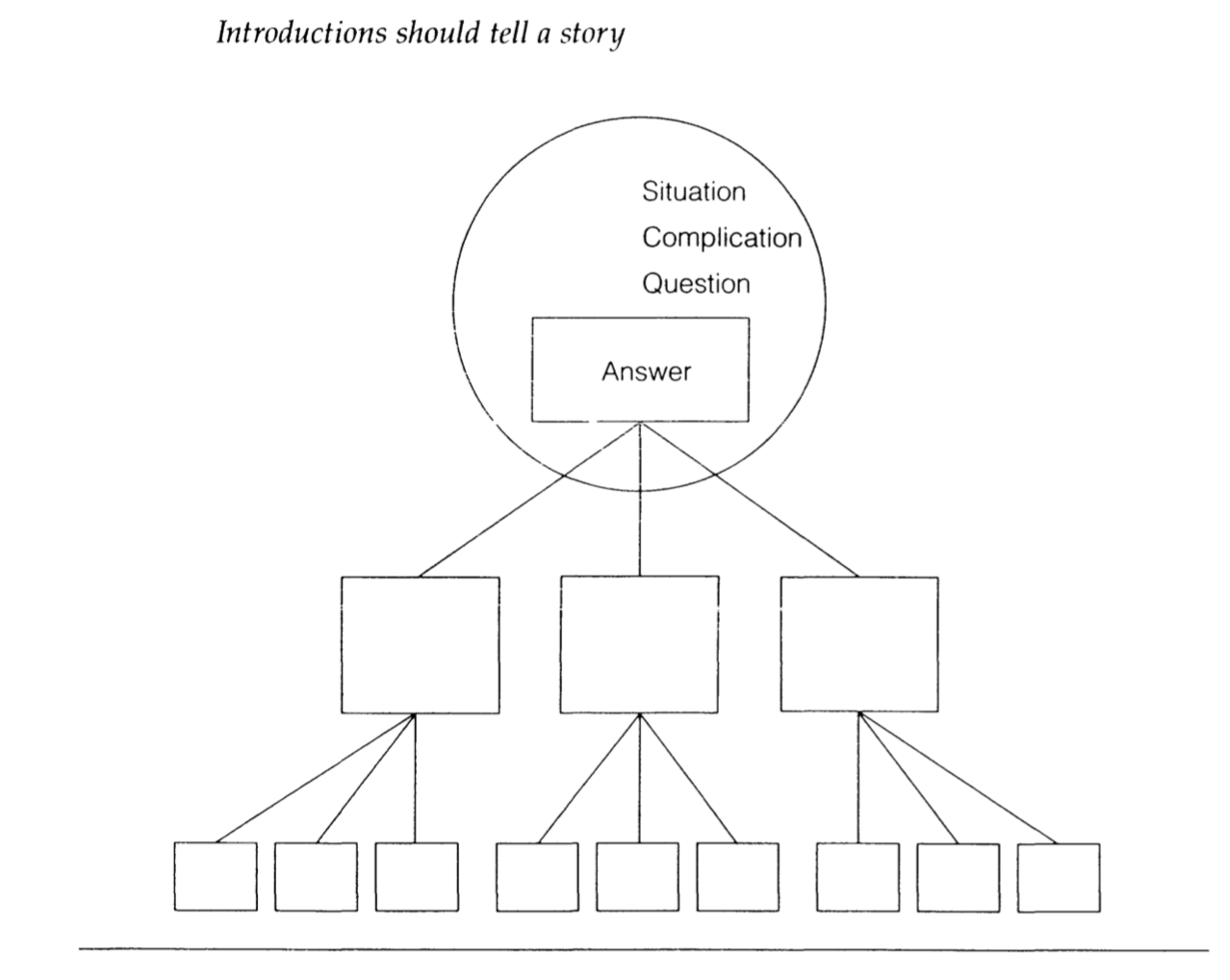

Specifically in writing, the introduction stands at the top of the pyramid. It should include the Situation, Complication, Question and Answer, together forming a classic storytelling pattern.

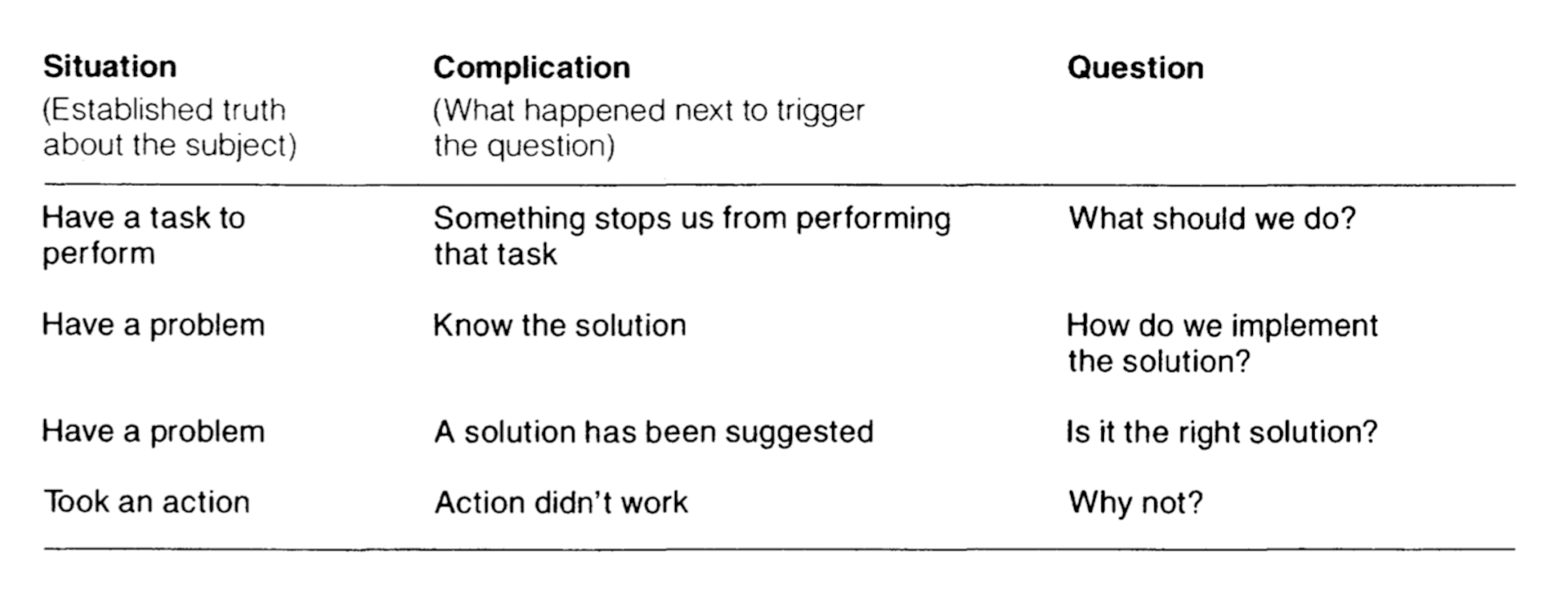

The Situation starts with a background statement which your conversation partner already knows about. The general expected response to this statement is for them to nod their heads, and say, “Yes, I’m sure that’s the case, and?” This response gives you the opening to insert the Complication. The Complication is more than a problem you want to address. It serves as a trigger for the Question. What will happen next in the story that leads to a Question. Check the examples below:

It is essential to follow the situation-complication-solution form of the introduction. However, the order of the parts can be varied according to the tone you want to establish.

In Barbara’s book The Pyramid Principle: logic in writing and thinking, she offers more details about structuring the Pyramid. If you are interested, it is a very worthwhile read. The three points I have mentioned in this article are just the tip of the iceberg.